The steering wheels, handbrake and gear are released for the excellent direct drive series.Nearly two years after the excellent Logitech...

Donald Trump. Photo: Paul Sancia/AP TTKamala Harris. Photo: Jacqueline Martin/AP TTThere are now only seven weeks until the US presidential...

It is estimated that up to one in ten elderly people in Sweden suffer from malnutrition. Of those cared for...

Talk through space with the new Garmin It's now possible to communicate with photos and voice messages via satellite with...

The municipality of Botkyrka, south of Stockholm, received 65 million Swedish kronor in government grants to stop new recruitment into...

During the seminar, the Ei task force will provide an update on the status of the ongoing government task and...

According to Nordea's chief economist Aki Kancharjo The economic consequences are not as great as expected for Finland. The economic...

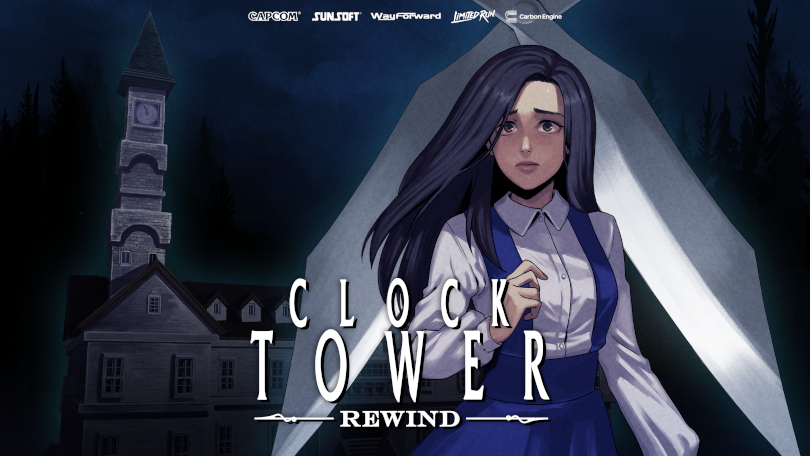

WayForwardA remake of the first game in Clock TowerThe release date for the series, which was announced last summer, has...

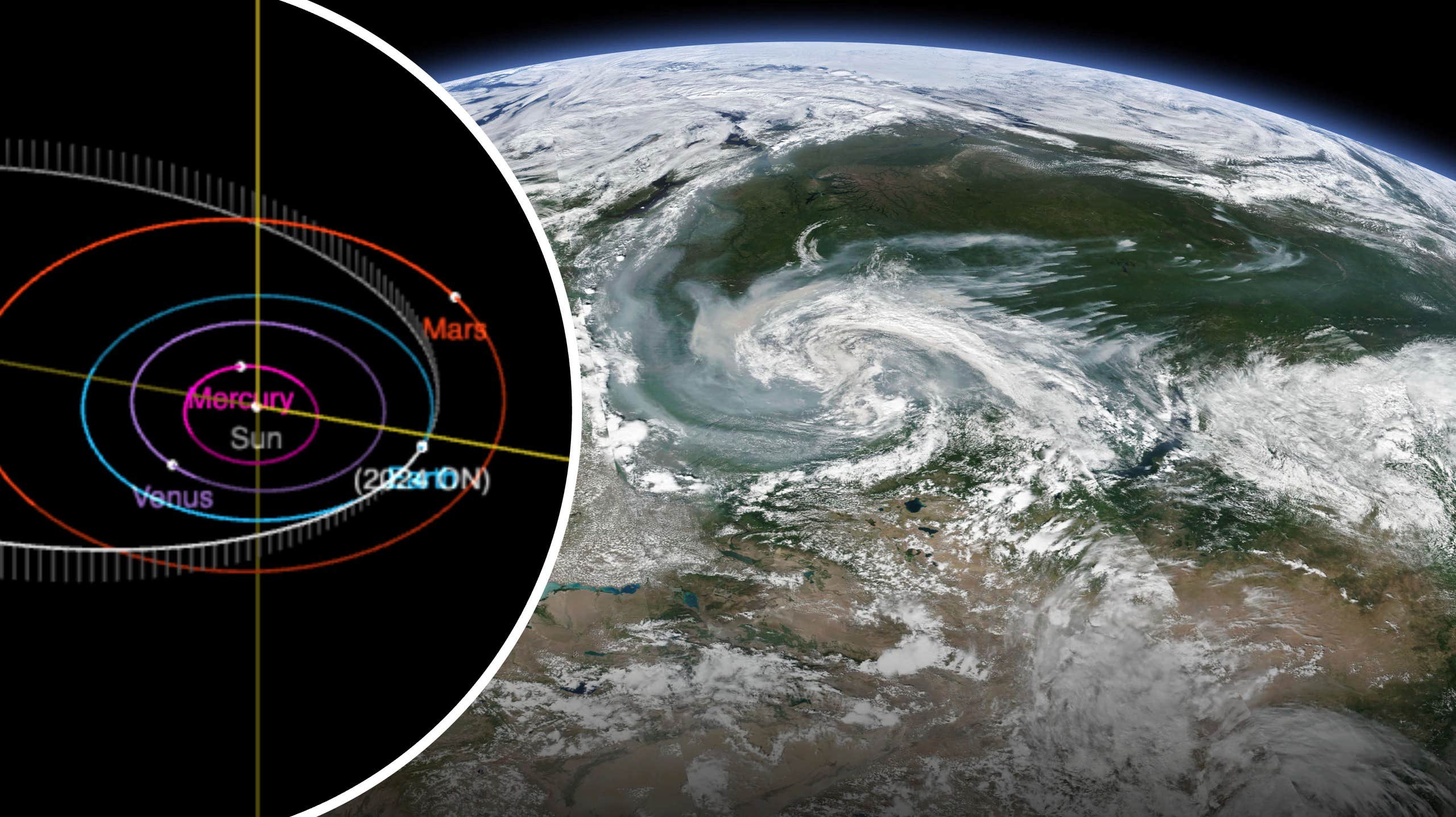

Satellite image of Earth taken in 2019. Photo: Joshua Stevens/AP TT News AgencyThe white line shows how close the asteroid...

Pale Honey is synchronized with the single "Over Your Head" from their critically acclaimed debut album "Pale Honey". Pale Honey...