In April last year, archaeologists supervising metro line 3 works made a special discovery. On Zuidlaan, at the level of Stalingradlaan, part of the second city wall of Brussels has been exposed. This can be read in the scientific journal ‘Brussels Pamphlets“.

It is the first time that one of the nearly seventy semicircular constellations has been exposed. Before this discovery, the only archaeological remains of the second city wall were the Porte de Hal and the fortress wall from the 17th century, which were discovered during the construction of the Porte de Hal metro.

© Heritage Brussels

In addition to the tower, the archaeologists also found “two relatively parallel sections of the wall”. Both discoveries have been stymied largely by recent developments, such as a concrete hatch on the west side and brick ducts running directly through it.

The second city wall of Brussels

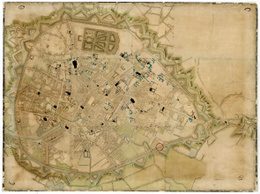

In the 14th century, both Brussels’ economy and population grew rapidly, forcing the city to expand and build a second wall. The difficulties of Ludwig van Male (Count of Flanders) and his forces in defending the city in 1356 may have been decisive in laying the foundation stone in 1357.

The second Brussels city wall was eight kilometers in circumference: twice as long as the first. The wall had about seventy semi-circular towers, two circular watchtowers, and was pierced with seven gates and two locks.

Although only the Halle Gate remains, many references can still be found in Brussels to the entry gates of yesteryear: the Halle Gate, the Naamse Gate, the Leuven Gate, the Schaarbeekse Gate, the Lakense Gate, the Flemish Gate, and the Anderlechtse Gate.

© Brussels Magazine

An important road departed from each of these gates, such as the road to Ghent. The eighth gate, Oeverpoort, was built in the 16th century. This allowed the canal, which connected the new inner port of Brussels with the Roble and Scheldt, to flow into the city.

The military defense wall turned into a corniche

At the end of the 18th century it was decided that the wall would no longer serve as a military defense and most of the entrance gates were demolished. Only Hallepoort has been preserved, since it served as a prison. Since then, the city wall is no longer a shelter, but rather a walkway with a beautiful view of the city.

Until Napoleon decided at the end of the nineteenth century – just as in Paris – to make room for a large avenue in the city, which the inhabitants of Brussels could move on foot or on horseback. This decision changed the shape of many of the city’s neighborhoods: new residential areas arose around the avenue, and the industrial area expanded on the north and west sides due to the presence of the harbour.

Over the years, pedestrians have been relegated to the sidewalks due to the large number of cars. Especially in the run-up to Expo 58, the Traffic Loop got a new look, when tunnels were added to divert large traffic into underground tracks. After another ten years, it was the construction of the metro that opened up the ring again, giving rise to the five corners of the Little Ring as we know it today.

Work on Metro 3 is far from over. Researchers believe there is a chance that more archaeological discoveries will emerge.